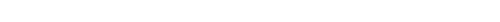

Goran Stefanovski

Stefanovski diagnoses the black hole of our time — the collective amnesia born out of the loss of one’s own story and the lack of interest in the story of the Other. That is the sickness of our contemporary Tower of Babel, our global world.

—Goce Smilevski, “Goran Stefanovski — A Playwright in the Tower of Babel,” Shoreless Bridges - South East European Writing in Diaspora

In Stefanovski’s drama all is not well, either outside in society or within the individual . . . Politics and history become characters incarnate.

—James McKinley, Introduction to HI-FI & The False Bottom: Plays by Goran Stefanovski

Stefanovski has created a specific and recognizable theatrical world, in which the characters of his plays are historically torn between east and west, between a poignant past and an unpredictable future, between obedience and rebellion.

—Naum Panovski, “Goran Stefanovski’s Sarajevo or Sara in the Horrorland,” Performing Arts Journal

Of Wild Flesh:

The pathogen metaphor (of ‘wild flesh’ growing around a hair inside the throat until its victim asphyxiates) is especially apt at describing imperialist intervention into cultures . . . [which] introduces a drastically one-sided power dynamic, to the profit of one and the undoing of another.

—Sofija Popovska, “Tales of Contagion: A Comparative Reading of Goran Stefanovski’s Divo Meso,” Asymptote

Of The False Bottom:

The creative impulse is manifested in Jacob who, with art as his starting point, will have to pass through the hell of madness to become a revolutionary in the recognition and naming of things.

—Vele Smilevski in “The Plays of Goran Stefanovski,” foreword to Goran Stefanovski: Selected Plays

Of Tattooed Souls:

In Tattooed Souls Stefanovski confronts his characters with the absurdity of their own existence in an environment where they don’t belong. In order to overcome this situation, the Macedonian in America is forced to create his own myths, which will somehow enable him to survive.

—Aleksandar Milenkov, Nova Makedonija

Of Ex-Yu:

Goran Stefanovski’s Ex-Yu about a woman seeking information about her father’s suicide during the Balkan war, is genuinely haunting.

—Michael Billington, The Guardian

Ex-Yu transcends exposition and news-cuttings to evoke a sense of loss that is poetically, humanly affecting.

—Time Out

Goran Stefanovski’s piece is the most adept . . . it eschews . . . mere re-enactment.

—Glenn Newey, Times Literary Supplement

Goran Stefanovski (1952–2018) was a leading Macedonian dramatist, screenwriter, essayist, lecturer, and public intellectual. He wrote for the theater, television, and film, work that was concerned with migration, post-communist transition and identity, as well as what it means to be human.

Patricia Marsh-Stefanovska is a linguist, an author of fiction and nonfiction works, and a translator from Macedonian to English of all kinds of texts, but especially the plays of her husband, Goran Stefanovski.

Introductory texts

STUBBORN DIGNITY by Chris Torch

SILYAN THE STORK FROM THE DEBAR DISTRICT by Slobodan Unkovski

Two passages from CASABALKAN

ZORA. Mick is a war reporter.

MICK. Was.

KONSTANTIN. What are you now?

MICK. A cynic.

KONSTANTIN. Welcome to the club.

MICK. Are you a member too?

KONSTANTIN. I was an enthusiast for a few seasons. I was shouting on my underground radio station for people not to give in to the nationalist beast.

MICK. The “underground radio station!” I’ve heard about you.

KONSTANTIN. My enthusiasm withered away. People went to their tribes. Multi-ethnic wasn’t cool anymore. Chauvinism was chic again! Overnight I became old-fashioned and cynical.

[Mick pours three glasses. They all drink.]

KONSTANTIN. Cheers.

MICK. Cheers!

ZORA. Cheers!

KONSTANTIN. To our future, whatever that means! [He drinks.] Do you know what my nationality is? I’m a Martian. That’s what I wrote under the heading “Nationality” in the last census. Zora’s a Martian too.

MICK. Rather nice.

KONSTANTIN. That’s what we thought at the time. We met at university. We fell in love. We got married. And for a few years we were very happy. I worked as a book designer. I thought the place of words was very important. There wasn’t Us and Them then. All of our friends were Martians. But we had enemies, and they sent us warnings! My father was a respected historian. He had a school named after him. With the monument to him in the schoolyard. A few weeks before the war started, we found the bust of my father lying in our living room. Ripped off the pedestal and thrown in through the window. Zora thought we should leave immediately. I told her not to be hysterical. I shouldn’t have done that.And then, coming home one night, I was rounded up with a group of citizens at a street barricade. A few jerks with guns asked us to declare whether we were Us or Them. I could have simply told them I was one of us. I could have said my name. Shown them my identity card. They would have let me go.

ZORA. What did you do?

KONSTANTIN. I said I didn’t understand their question. I refused to answer it. I asked them who gave them the right to ask such stupid questions. I said I was one of Them.

MICK. What did they do?

KONSTANTIN. They hit me in the head with a rifle butt. When I came round, I was in a camp with Them. I had plenty of time to think about it all and then say who I really was. But I was half-blind. Who was I supposed to ask for mercy?The people who put me there? Were they really my people? I was one of us, imprisoned with all of them. Now I know what we did to them because we did it to me. Later, they realized I was the odd man out. They let me go.

PURCHASE

** Free shipping for all international orders

Softcover — ISBN 978-1-942281-36-8 — 339 pages